The Resurgence of Nuclear Power: A Second Chance for Britain’s Energy Sector?

The urgency surrounding Britain’s nuclear energy landscape was starkly highlighted by the energy secretary’s remarks in Parliament. “The British nuclear power programme has been in decline over the last decade,” he stated, emphasizing the necessity for immediate action to reverse this trend and stabilize the industry.

Interestingly, this perspective echoes comments made by David Howell, a notable member of Margaret Thatcher’s cabinet, nearly 50 years ago in December 1979.

Howell had instituted a plan intended to rejuvenate the nuclear industry, proposing the construction of ten new nuclear power stations, one per year from 1982. He expressed confidence in the ambitious goals laid out before Parliament.

However, only Sizewell B, which started operations in 1995, was completed from that initial plan. Since then, no new power stations have come online.

This isn’t due to a lack of ambition. Three decades after Howell’s plan, Ed Miliband announced another similar initiative during his first tenure as energy secretary, proposing ten new plants. Yet, upon returning to the energy department last summer, only one project, Hinkley Point C, had progressed.

Hinkley Point C has faced significant delays and budget overruns, with completion now expected in 2031 and a projected cost of £46 billion, making it the priciest power project globally.

On June 11, Miliband is set to endorse Sizewell C in Suffolk, which has already benefited from £8 billion in public investment, with groundwork already underway. Additionally, he will unveil plans for a new wave of small modular reactors (SMRs), which are compact nuclear generators anticipated to play a pivotal role in the future of energy production.

These SMRs promise to be more affordable and quicker to construct, with hopes of delivering power to homes by the early 2030s. Yet, caution remains as no prototypes have been built anywhere yet.

So, why has constructing nuclear power facilities proved so challenging in the UK? With the industry’s history of safety concerns and soaring costs, should we even pursue new nuclear options?

The Energy Crisis

Over the last fifty years, nuclear power has been touted as a viable solution to Britain’s energy challenges. Proponents argue that it can support intermittent sources like wind and solar while reducing dependency on oil-rich nations.

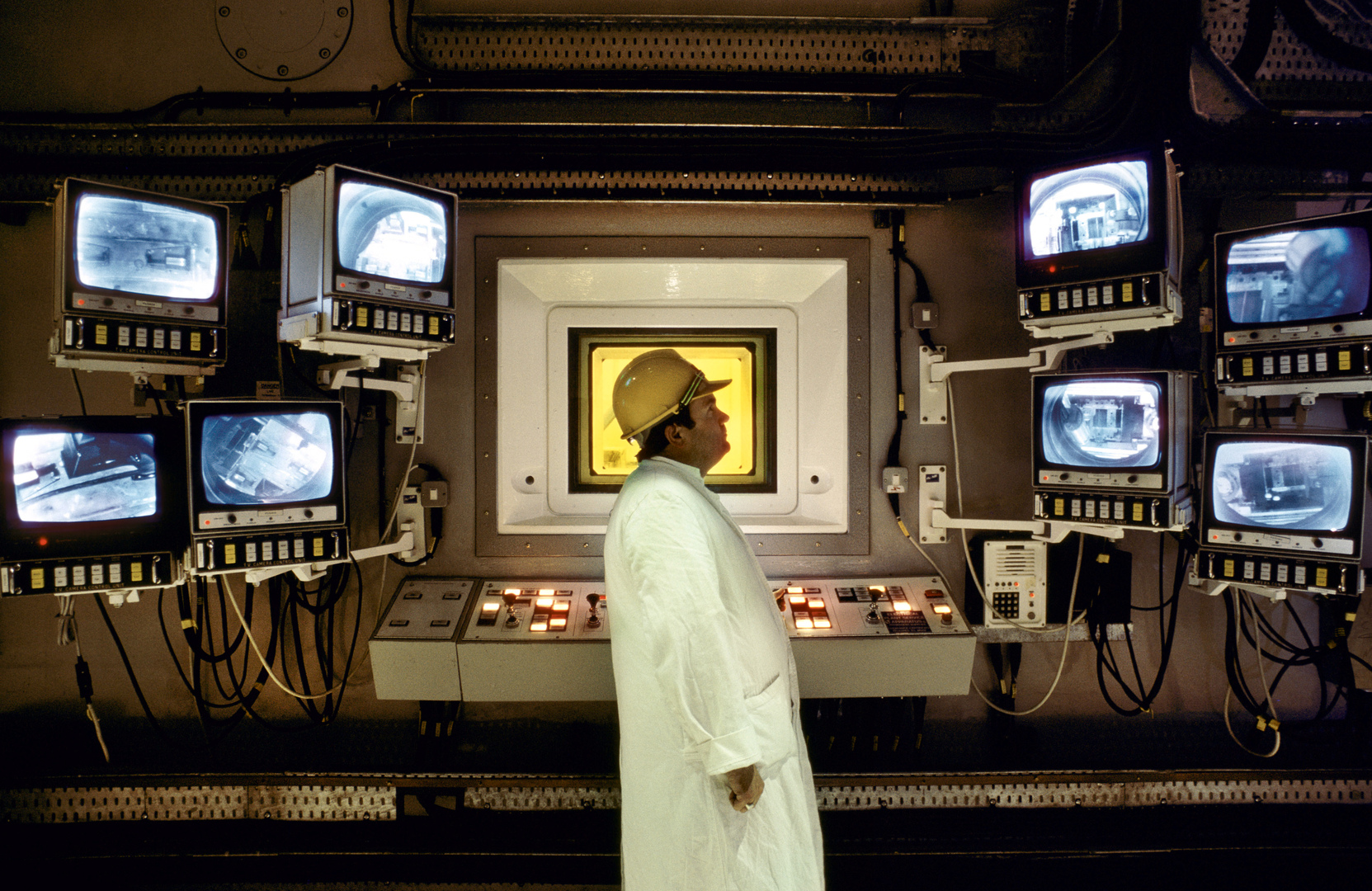

Britain was once at the forefront of nuclear technology, inaugurating the world’s first commercial nuclear power station, Calder Hall, in Cumbria in 1956. The subsequent decades saw a proliferation of reactors, supplying steady electricity to the nation.

In 1997, 17 nuclear stations were operational, contributing 27% of the UK’s electricity needs. But the discovery of inexpensive gas in the North Sea led to a significant decline in nuclear investment during the 1990s, with only five aging facilities still operational today. Four of these are expected to be decommissioned by 2030.

The 2011 Fukushima disaster prompted worldwide scrutiny of nuclear safety, echoing fears that arose from previous incidents such as Three Mile Island and Chernobyl. Environmental concerns around nuclear waste persist due to the lengthy half-life of uranium-235, complicating storage solutions.

In spite of these challenges, Miliband plans to revitalize the UK’s nuclear sector, advocating for new planning regulations to facilitate the construction of nuclear power stations nationwide.

Growing Awareness

While similar promises have been made before, experts perceive a renewed urgency from decision-makers this time.

Tim Gregory, a nuclear chemist at Sellafield, emphasizes the growing realization of the energy demands of modern society, noting the significant electricity needs of electric vehicles, heating systems, and emerging technologies like artificial intelligence.

The initiative to achieve net-zero carbon emissions heightens the urgency for nuclear expansion. With the closure of Britain’s final coal-fired plant last year and plans to eliminate gas-generated power by the end of the decade, reliable energy sources are critical.

Gregory questions how the UK can simultaneously meet significant electricity demands and achieve net-zero emissions, suggesting that nuclear energy remains a logical part of the solution.

Critics argue that Miliband’s commitment to renewable energy might overshadow the role of nuclear in the energy mix, referencing his anti-nuclear family background. However, supporters contend that his green principles reinforce his resolve to advance nuclear initiatives.

Miliband acknowledged a transformation in his stance towards nuclear fuel during a 2009 speech, recognizing that climate change should reshape public perceptions about nuclear energy’s role.

This sentiment is echoed globally, with former adversaries of nuclear energy now recognizing its potential. In many instances, the drive for energy independence and resilience to geopolitical conflicts fuels this shift.

International Developments

In the context of recent global events, including the Ukraine crisis and the pandemic, there’s a burgeoning desire to reduce reliance on foreign energy sources, according to Andy Champ, who oversees the UK nuclear programme for GE Hitachi.

Many nations are re-examining their nuclear policies. France, whose extensive nuclear infrastructure remains crucial, recently finished its first new reactor in 25 years. The US also has initiated the construction of modern reactors, though with significant cost overruns.

As safety concerns recede, a pragmatic approach to nuclear energy is emerging. Proponents highlight that nuclear energy has resulted in fewer fatalities than renewable energy sources like wind.

Countries such as Germany and Denmark, which historically opposed nuclear projects, are reconsidering their stances. Japan is also weighing the revival of its nuclear plants to lessen dependency on fossil fuel imports.

Public support for nuclear energy is increasing globally, significantly rising in the US as electricity demands grow, particularly from data centres and other energy-intensive sectors.

As a pressing national competitor, China currently has more nuclear reactors under development than any other nation. They have initiated construction on numerous new units since 2020, and South Korea continues to expand its nuclear capabilities and export technologies.

Small Modular Reactors: The Future?

Britain has the chance to regain traction in its nuclear sector. Sizewell C is intended as a duplicate of Hinkley Point C. Yet, industry insiders warn that timely decisions are critical to capitalize on available expertise.

Approximately 12,000 individuals are employed at Hinkley Point, with another 14,000 engaged in supporting roles across the UK. If Sizewell launches promptly, it could facilitate the transition of its workforce from Somerset to Suffolk. Delays, however, risk these skilled workers seeking opportunities elsewhere.

Financing remains a significant hurdle. Hinkley Point C, initially projected to cost £17 billion, is now estimated at nearly triple that amount.

Traditionally, large projects were deemed economically favorable due to scale, but the required investment of over £40 billion for a single nuclear site is daunting. It can take over a decade before returns on such investments are realized.

SMRs could offer a viable solution, producing around 300 megawatts each—a fraction of the output from conventional reactors. They also occupy significantly less space, allowing for multiple installations on existing or repurposed sites.

Great British Nuclear is preparing to announce the manufacturer selected to construct the UK’s first SMR, which could also be the first globally, as four competitors vie for the project.

While visions of widespread SMR distribution abound, experts caution against impractical expectations. The initial rollout will primarily focus on established sites, with plans to potentially install numerous SMRs to match Hinkley’s total output.

The financial implications are promising, with estimates suggesting each SMR could cost approximately £3 billion, significantly lower than traditional plants. Yet, Champ notes that efficiencies can only be fully realized with large-scale construction of multiple units.

If a series of SMRs are constructed across the UK, a critical challenge remains: the management of spent nuclear fuel and radioactive waste. Nuclear Waste Services is currently seeking a location for a comprehensive underground waste disposal facility.

Three potential geological sites have been identified in Cumbria and Lincolnshire. Yet, even with local approval, a functioning site may not materialize until the 2050s, with costs projected up to £53 billion.

Tim Gregory, from Sellafield, remains optimistic. “We have faced challenges before and can navigate this one as well. Addressing the energy crisis can lead to solutions for economic, environmental, and humanitarian issues. Nuclear energy can facilitate these resolutions,” he asserts.

Post Comment